This is the starting post of a (hopefully) long series on consistency in computer systems. I always had this problem of not being able to get everything about consistency in my head. There are many consistency models (linearizable, strict serializable, snapshot isolation, …); I always forget what those terms mean, and it’s not always my fault they are not defined consistently.

This post is based on “The many faces of consistency”. It’s very easy to read, and I suggest you read the actual paper. I find it a very good paper to use as a starting point so that we don’t get into much detail at the start. I would appreciate any feedback or pointing out my mistakes; I’m writing so that I can also learn in this process.

What is (in)consistency?

- I open Twitter and like a tweet, but the tweet doesn’t show my like after I refresh.

- You updated the DNS entry on your website, but clients are still unable to access the website.

- I send some money to a friend; I see it is not in my account anymore, but my friend hasn’t received it.

All these cases are examples of inconsistency in computer systems. But what causes all these? The devils of data replication (when we have several representations of the same data item and they end up different) and data sharing (when multiple people use the same data item simultaneously and disrupt each other).

The paper argues that there is no single answer to what is considered consistent. In the case of DNS, we are okay with the entries propagating eventually through the Internet, but we are not okay if we buy a flight seat and somebody else also reserves that seat. It is essential to identify what is okay in a system so we can build a system that satisfies our consistency requirements and doesn’t go beyond or doesn’t do less than needed. A higher consistency guarantee can sometimes result in lower performance, which might not be required (think twice).

Consistency Types

The paper’s main idea is that there are two types of consistency: State Consistency and Operation consistency.

State Consistency

State consistency means that we want some properties to hold (invariants) in the system. For example, I always want the money sender and money receiver to have the same total money after a money transfer. These are mostly related to the context of the application. These invariants might even need to hold only after some time passed. For example, in the DNS example, we would like all the DNS servers to eventually have updated entries. I think how the paper defines state consistency maps well to the Safety and Liveness properties of systems. Safety means that a bad state never happens, while Liveness means something good will eventually happen.

Operation Consistency

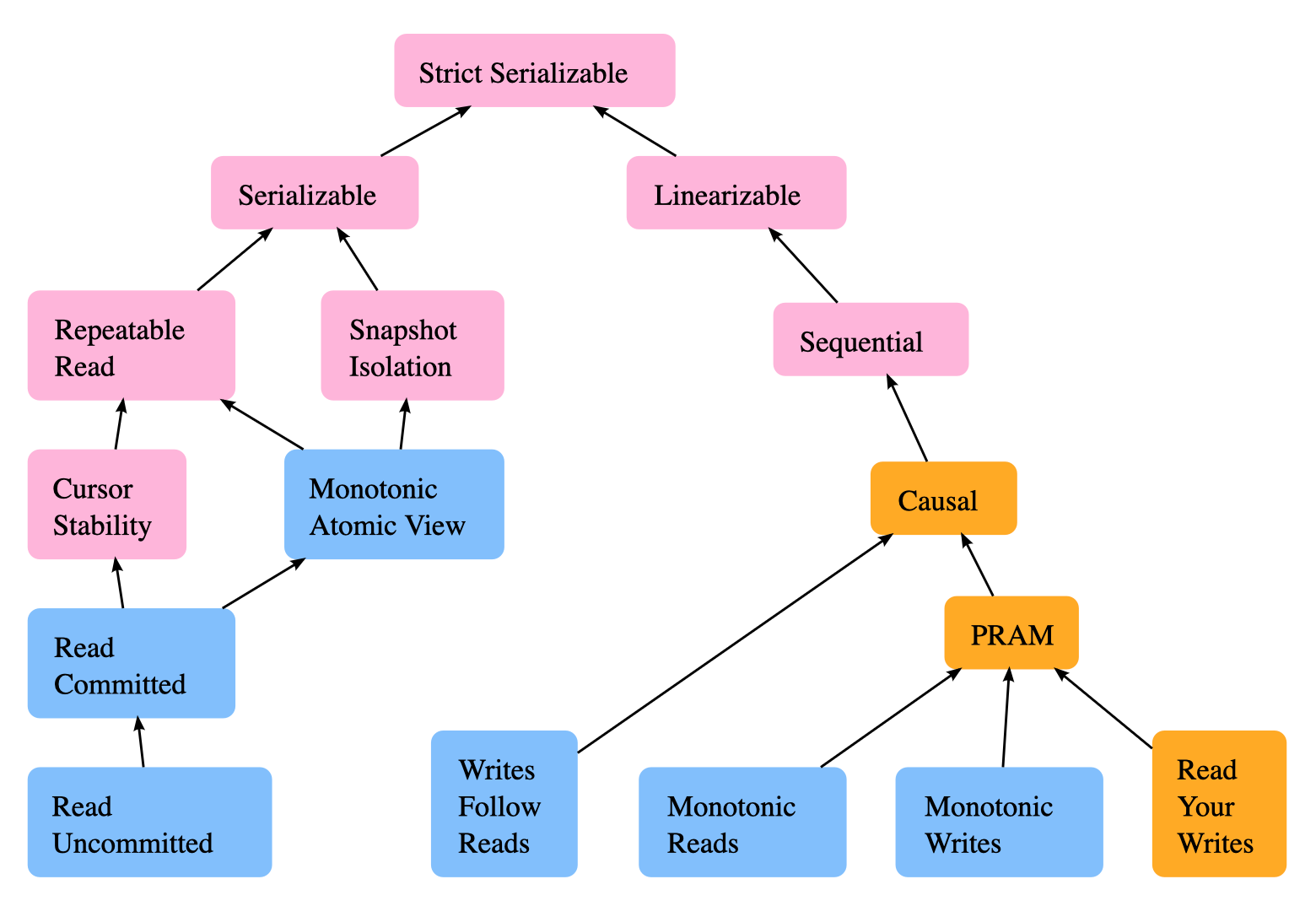

It talks about how we should observe the client operations. For example, we would like to read/write operations to a database as if they happened in sequential order (definition of Serializability). These are commonly less application-dependent and do not care about the system’s internal state. The paper argues that operation consistency happens at a higher level of abstraction, and it only cares about the effects of the operations, not the internal state. The following are some types of operation consistency models by Jepsen:

State vs. Operation Consistency

So, the question is, how do these two relate to each other, and when should we use which one to think about a system?

Level of Abstraction

Operation consistency is at a higher level of abstraction than state consistency. It doesn’t care about the internal state and only observes the outcomes seen by client operations. The interesting point here is that a system might not be state-consistent, but it can hide the inconsistencies from the clients, being operation-consistent.

An interesting example is a storage system with three servers replicated using majority quorums, where (1) to write data, the system attaches a monotonic timestamp and stores the data at two (a majority of) servers, and (2) to read, the system fetches the data from two servers; if the servers return the same data, the system returns the data to the client; otherwise, the system picks the data with the highest timestamp, stores that data and its timestamp in another server (to ensure that two servers have the data), and returns the data to the client. This system violates mutual consistency, because when there are no outstanding operations, one of the servers deviates from the other two. However, this inconsistency is not observable in the results returned by reads, since a read filters out the inconsistent server by querying a majority. In fact, this storage system satisfies linearizability, one of the strongest forms of operation consistency.

Which one to use?

First, think about the negation of consistency: what are the inconsistencies that must be avoided? If the answer is most easily described by an undesirable state (e.g., two replicas diverge), then use state consistency. If the answer is most easily described by an incorrect result to an operation (e.g., a read returns stale data), then use operation consistency. A second important consideration is application dependency. Many operation consistency and some state consistency properties are application independent (e.g., serializability, linearizability, mutual consistency, eventual consistency). We recommend trying to use such properties, before defining an application-specific one, because the mechanisms to enforce them are well understood. If the system requires an application specific property, and state and operation consistency are both natural choices, then we recommend using state consistency due to its simplicity.

How different disciplines view consistency

Distributed Systems talk about either state or operation consistency. In Database Systems, consistency refers to state consistency (C in ACID). The “A” and “I” in ACID are forms of operation consistency. In Computer Architecture, consistency refers to operation consistency.