This post is based on Maurice Herlihy and Jeannette Wing’s paper where they formalize linearizability. I often confuse linearizability with strict serializability. This post hopefully clarifies this for myself and the readers. I will write a post later about serializability.

Problem Statement

Concurrent data structures have important applications, but we need a way to identify what is a correct behavior of them. A concurrent data structure has a set of supported operations $P$ and a set of possible values $V$. Clients concurrently operate on $D$, but we would like to have reasonable behavior. Linearizability allows for reasoning about the history of operations on a concurrent data structure or other shared data objects.

An intuitive definition of linearizability

Intuitively, a linearizable history of operations on a concurrent data structure satisfies two conditions for every object:

- Each operation appears to take effect instantaneously.

- The timing order of non-concurrent operations is preserved. If an operation $A_j$ happens later than $A_i$ it observes the effects of $A_i$ on the data structure.

Linearizability only considers single objects. It guarantees that the operations appear to happen in their sequential order.

Semi-Formal Definition

Let’s first define a history of operations. A history is a finite sequence of operation invocations and response events performed by different processes. Each event is a $x,op,P$, where x is the object, op is the operation, and P is the process issuing the operation. The event has an invocation time where it starts and a response time where it finishes its execution. Sequential history is one that each invocation is immediately followed by a matching response; There are no interleaving events.

Linearizability is defined on a history of operations. We care about the partial order on non-concurrent (not interleaving) events. We define a history $H$ to be linearizable if its partial order can be extended to a sequential history respecting the real-time order. So, non-concurrent operations should respect the real-time order of operations. We don’t care about the order of concurrent operations. They can happen either way. But if an operation ends before another operation starts, we want the second operation to observe the changes of the previous operation.

Examples

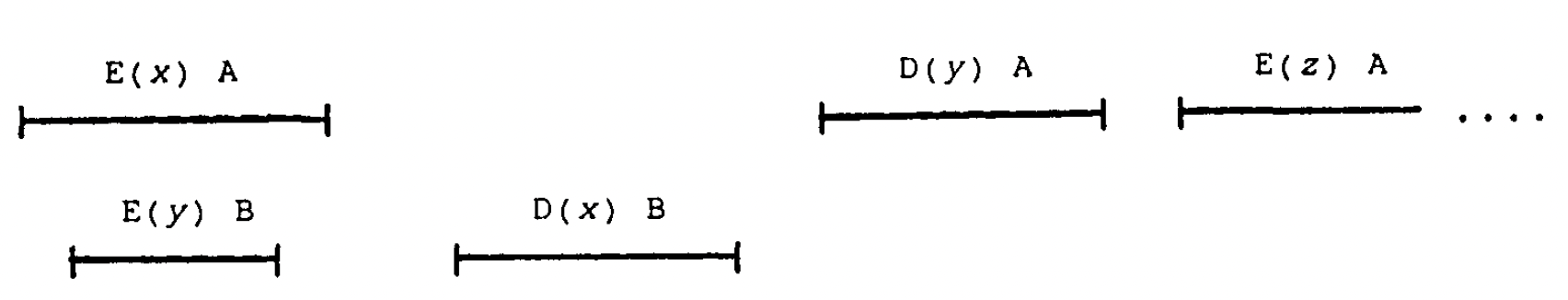

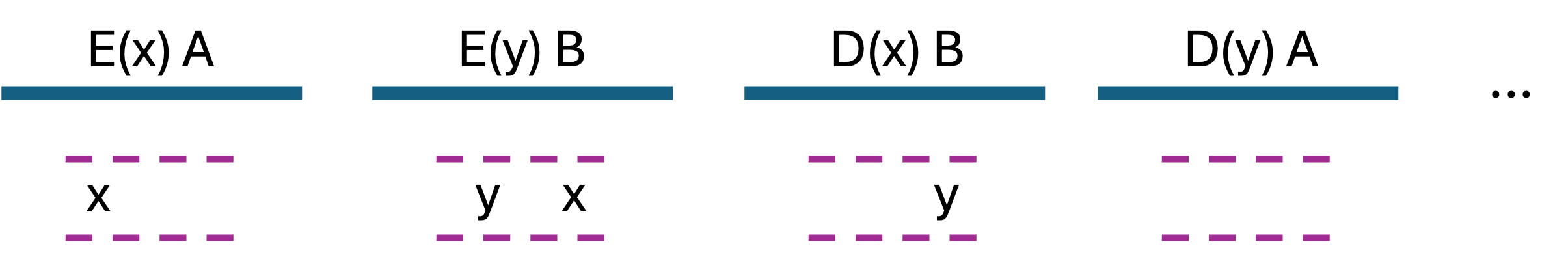

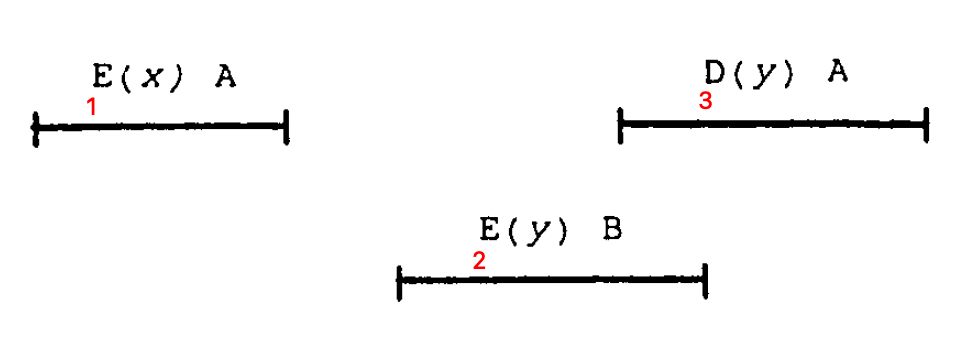

Here are some examples to help us reason whether a history of operations is linearizable. The examples are about a queue data structure that operations concurrently enqueue (E(x) means enqueue of object x to the queue) and dequeue (D(x) means dequeue of object x from the queue) to it.

History 1 (Linearizable)

Linearized History:

Linearized History:

This is a linearizable history because we could maintain the partial order of the non-concurrent operations and extend it to a valid sequential order.

This is a linearizable history because we could maintain the partial order of the non-concurrent operations and extend it to a valid sequential order.

History 2 (Not Linearizable)

This history is not linearizable. Event 1 should happen at first since it came before the other two concurrent events. We have two possible options for the other two events: 2 before 3 or 3 before 2. If 2 happens before 3, then we will have x in front of the queue while event 3 wants to dequeue y from the queue. If 3 happens before 2, it is also wrong since we are dequeuing y while x is in front of the queue.

This history is not linearizable. Event 1 should happen at first since it came before the other two concurrent events. We have two possible options for the other two events: 2 before 3 or 3 before 2. If 2 happens before 3, then we will have x in front of the queue while event 3 wants to dequeue y from the queue. If 3 happens before 2, it is also wrong since we are dequeuing y while x is in front of the queue.